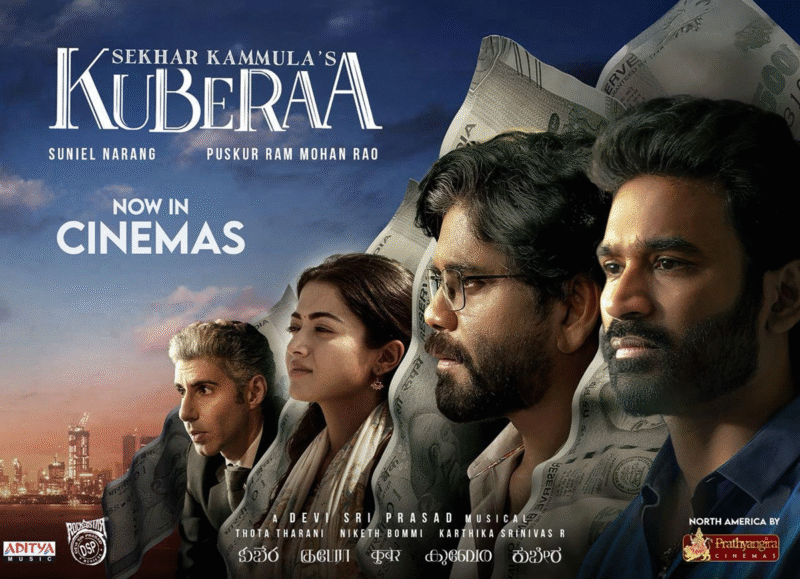

Kuberaa: Oblivion Irony

Star Cast: Dhanush, Nagarjuna, Rashmika Mandanna, Jim Sarbh, Dalip Tahil, Sayaji Shinde and Others

Music Composed by Devi Sri Prasad

Cinematography by Niketh Bommireddy

Edited by Karthika Srinivas

Directed by Sekhar Kammula

If you haven’t watched Kuberaa yet, watch it first then come back and read this short opinion. (Spoiler Alert!)

Sekhar Kammula is the only Telugu director who did not resort to a God complex in storytelling. He has always portrayed his leading characters as humans, and even in Kuberaa, with big stars, he treats them solely as characters. Not for a second does he attempt to depict Deepak or Deva as gods saving humans from Rakshasas – Niraj Mishra, politicians, or the system. He could have easily done that, but he didn’t. However, he fails to fully grasp the real-world premise in setting up this financial ruckus drama, which spirals into chaos at every step.

In Leader [2010], he tried to showcase an ideal man who could become an ultimately honest leader of a country or state within our system, but he never really cared to expand on it. The same problem repeats in Kuberaa as well. He seems unable to decide whether he’s against privilege, for it, trying to reflect the real world devoid of ideological framing, or aiming for a deeper discussion on the convoluted, hypocritical nature of a system created by humans, for humans, and favoring those who enjoy power. If you try to make it about everything, then it also needs to offer a solution to the problem. A reflection in the mirror will show whether you appear as you wish in a certain dress or a certain look. But if that reflection is distorted, you end up feeling just as broken as the mirror before you.

Kuberaa starts off with a scam being born and then ends with that very scam benefitting a slum boy making him “Slum-boy [not wanting to use dog for a baby] Millionaire” upon birth. We watch a privileged crook, convinced the world belongs to him, prepared to kill, steal, cheat, and commit every imaginable crime to take it all. By the end, we see a young boy fighting against all odds even the death, which succumbed his mother, to see the day of light. Metaphorically, Sekhar Kammula plays an uno reverse: the privileged man, who contributed nothing and even plotted the boy’s murder, ironically becomes the very reason the child inherits ₹10,000 crores. The irony of this twist seems to have thrilled the director so much that everything else fell to the back seat.

Nagarjuna, as his character’s name suggests, is Deepak – the light in Dhanush’s and the young boy’s life. He even ends his life like a deepak, passing on the flame. Deva in mythology was created by Vishnu, Shiva, and Brahma as the treasurer of the Devas, after realizing that Amaravati [not the AP capital] would always be under threat from Asuras. They needed a repository where wealth could be protected, beyond the reach of Asuras and directly under divine care, thus Kuberaa was born. The treasurer of the gods, and god of wealth, accumulated so much that he once lent money to Vishnu in his Srinivasa form. So, a bank of gods. Now, what does Dhanush do in the film? He fights a crime syndicate of Asuras, rises like a god for beggars like himself, and then gives everything to Kuberaa – a Devatha. You remember when I said Sekhar Kammula doesn’t resort to a god complex? He still doesn’t, but metaphorically, he came close to crafting one.

The problem lies in that very same thing. He framed it as a battle between a pure soul, worthy of becoming a god – a human caught in the crossfire, and a pure evil force, an Asura. What could the outcome of such a battle be? In the Ramayana, when the Devas and Asuras clashed, Dasaratha, the human king sided with the Devas. He was rewarded with a mesmerizingly beautiful woman, Kaikeyi, who aided him in battle. He granted her two boons, which ultimately led to a curse he brought upon himself. He died in anguish, waiting for the son he loved literally to death. Now, in Kaliyuga, a modern-day Dasaratha, once again for the sake of his family, helps the Rakshasa. He tries to redeem himself and rewrite the course out of remorse and ends up facing the same fate, though this time with a sense of peace, knowing he helped a just cause. While Ramayana became a timeless epic, this tale ends up feeling convoluted, unnecessarily lengthy, preachy, and much like that distorted reflection in the mirror.

Also Read: Love Story

Why? A bit of basic research into how a CBI officer could face corruption charges or get into trouble simply for being honest and to what extent the system can actually target someone of caliber, would have helped him design Deepak more effectively. To transfer someone’s money, a power broker is usually enough, a CBI officer isn’t required. Especially not one who specializes in financial crimes, such individuals aren’t easily disposable assets. People with high morals tend to step aside when power is out of reach, and Deepak needed to be that kind of person within the system, not outside of it. How could a multi-billionaire who routinely donates party funds and handles large transactions not know whom to trust for shell companies or how to move money discreetly? Are CBI officers really needed for something that petty? Now, imagine this: ₹10,000 crores go missing during a transfer, and the minister brings in Deepak to track it down. This same Deepak turns out to be Deva’s childhood brother, a fellow orphan who escaped life on the streets to become a CBI officer. Doesn’t that version of Kuberaa hit harder with the same theme, but deeper emotional weight and stronger internal logic.

Deva is a reactive character – he lives within his circumstances and survives them. Life has shaped him that way. Now, imagine him trying to accumulate this wealth of Rs.10,000 crores and save it for his people, doesn’t his character’s motivation and purpose become more clear straight away rather than becoming random? He could still be beggar Deva, still involved in the scam, and it could remain Deepak’s story, he’d just be the one deciding who truly deserves the money. Why can’t a narrator like Sekhar Kammula think along those lines? Deepak could still be operating under the influence of a minister, someone who once saved his job and mellowed him down after a career marked by fear and integrity. This isn’t an aspirational rewrite, it’s embedded in the original script itself. After all, Sekhar introduces Deepak as a CBI officer known for uncovering ₹1,000 crores in financial crimes. That’s his starting point.

This is all a balancing act. In a film where your characters look plain, you tend to make them more interesting by crafting a screenplay that offers something engaging for common audiences. Sekhar Kammula got carried away in creating situations to show a beggar slowly growing “reactively clever”, but the system shouldn’t grow dumb for Deva to appear smart. Yet that is the end result of this film. The system starts behaving as if it’s clueless about tracking someone running with huge amounts of money within the country. Let him be a beggar, but go stand on the roadside, talk to someone, and you’ll hear what they aspire to and how cunning they, too, can become as circumstances change. The movie wants to be about class differences, character differences, and motivational contrasts, but it ends up being the tale of an idealistic filmmaker trying hard to tell a story with honesty without rising above his own viewpoint of society or the story itself. This isn’t a comment on his abilities, but it’s important to broaden your vision. Otherwise, no matter how well Dhanush, Nagarjuna, Devi Sri Prasad, or Niketh Bommi perform, it all feels like a dry plate of undercooked chicken when a feast is promised with such interesting ingredients. It’s just like starting a journey with a destination in mind, only to exclude it entirely from your plan because the route you chose has a waterbody due to rain instead of building a bridge to cross it.

Theatrical Trailer:

Recent Comments