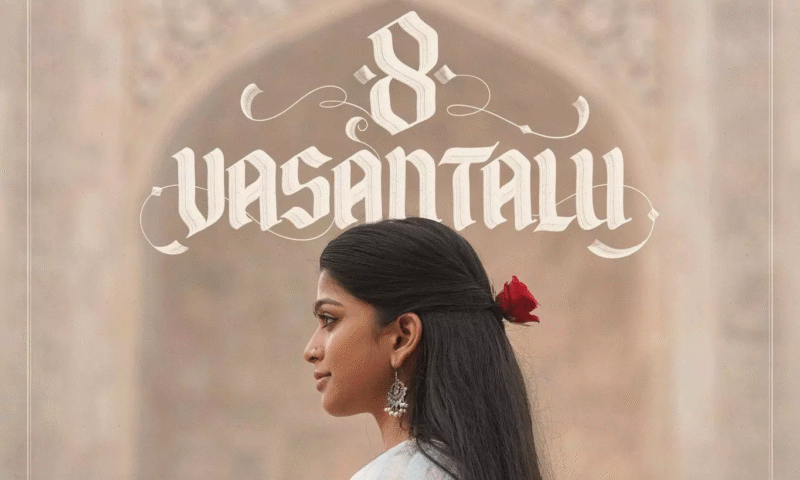

8 Vasantalu: Unrelenting Quest

Star Cast: Ananthika Sanilkumar, Sumant Nitturkar, Ravi Theja, Kanna Pasunoori, and Hanu Reddy

Music Composed by Hesham Abdul Wahab

Cinematography by Vishwanath Reddy

Edited by Shashank Malli

Directed by Phanindra Narsetti

Let me start with a side note. I had almost decided to only write about movies that truly have something worth talking about, instead of those that just bring out the basher and sarcastic humor in me. But 8 Vasantalu made me set that decision aside and write. From this introduction, you can probably guess how I feel about the movie. To put it simply in one line – not worth your time. If you’d like to read my full opinion and understand why I feel this way, then beware. There’s not much to spoil, you can guess it easily. Still, spoiler alert.

Love that undermines you, never lets you grow or be yourself as an individual, hurts your self-respect, and in no way fulfills you is never love.

This is the point Phanindra Narsetti makes in the entire movie. He showcases four variations of love: motherly, friendly, consuming, and empowering. Shuddhi Ayodhya is a character who can be equated to Mother Earth – someone who relentlessly provides, even if you hurt her or dig holes into her soul. She continues to rotate in this endlessly expanding universe around a star that attracts and nourishes her with energy, all while revolving around herself. She knows how to protect us by filtering out harmful radiation and offering only the light we need. Then, she allows that energy to blossom and gives us more ways to learn and evolve. This kind of motherly love is seen in Shuddhi Ayodhya’s actions toward her friends. She is willing to give up her riches for their well-being and even take a stand against the world for her Guru.

We can equate this story to many tales in mythology where Mother Earth is forcefully taken or attracted by evil forces or rakshasas, from whom only Lord Vishnu can rescue her. He takes different forms and becomes the worthy one to save her each time. In this case, there’s an inverted retelling: Sita waiting in Ayodhya for her Ram. First, Ravan draws her attention, and then she eventually finds her man, who is always nearby yet distant from her heart. He needs to become a writer, someone worthy enough to wield Shiva’s Bow and take her hand. Not such a far-fetched theory, as she is Shuddhi Ayodhya, living in Ayodhya Nilayam, with a fatherly figure who isn’t her biological father. Even Lord Rama had a sister, Shanta, and here we have Sandhya. Sanjay, then, can be associated with Vishnu and Shiva as triumphant warriors.

Also Read: Manu [2018] Review

Coming to Friendly love, she is ready to help an unknown person and has the qualities of being your best friend at every stage of life. Consuming love is associated with Varun’s arc, while Empowering love is represented through Sanjay. Even her mother becomes empowered, moving beyond her obsession to fulfill a single wish for her beloved daughter. The return of favor to the motherly figure in the group is made by Karthik, who helps her understand that sacrifice is not an option when it comes to lifelong happiness. But that idea doesn’t translate well to the screen, as he could have simply sent a video message to Shuddhi’s mother instead of flying back. What happened to his family? Where did Varun go? There are no answers. Still, all said and done, these elements on paper sound brilliant.

Even the color theories – whites, dark tones, symbolic shots, and the use of rain – all point to talent, but that talent lacks the skill of execution. You see Shuddhi wearing light colors, while Varun wears dark ones, and she is introduced in white. Up until the breakup, she wears various shades of white mixed with lighter, brighter tones, while Varun moves from darker hues to lighter ones and eventually returns to darker shades. After the breakup, her wardrobe shifts to darker hues, while Sanjay moves into whites and lights. This reversal is clearly intended to show who carries the emotional weight and who appears purer in love. Symbolic shots involving roses and the use of rain reflect her inner turmoil, like Mother Earth’s tears under the weight of emotion. It’s one thing to understand a concept and try to implement it, it’s entirely different to execute it effectively. Mani Ratnam achieved such success because he strives to find believability, even in surrealism.

Watch his Raavanan [2010] and Kadal [2013] – both films carry surrealistic elements, yet they remain grounded. The symbolism is subtle, woven into the background, and the narrative never loses its momentum. But when the story halts, it becomes Thug Life. Take Thalapathi [1991], for instance. There’s a scene where the mother doesn’t know her son is alive, and Rajinikanth doesn’t realize his mother is right beside him. Meanwhile, the fatherly figure knows they are related. He works silently to bring them together, even though they are like opposite poles, still longing for each other. When they hear the train horn, it pulls them back into their shared trauma, while the one confirming their bond silently shares their pain. That’s how symbolism works. Everyone remembers the iconic sun shot behind a sorrowful Rajini as he lets go of his love. His character never feels superficial. Even though the dialogues carry Mani Ratnam’s signature style, they remain colloquial and believable for the character. We don’t see Rajini giving long speeches to summarize his inner turmoil, he keeps it simple and relatable. Still the poetic quality of Mani’s visual frames makes us revisit the film and keeps the magic alive.

If a person claims to understand what Mani Ratnam’s films stand for, can’t he see where his own writing and execution are going wrong? You cannot narrate a love story like a thriller filled with twists. You need to allow the audience to feel the emotion rather than sending them into chaos. The first half feels like a rewatch of 1940s and 1950s subdued commentary, while the second half feels like 1980s rebel poetry. There’s nothing contemporary in a setting that tries to be as complex and as poetic as the dance form it’s named after. Characters never speak casually everything is phrased as an exaggerated metaphor. Take, for example, a supposedly brilliant writer saying, “Nenu Enugu Cheruku panta mida paddattu pusthakala mida padipoya” [I fell on books like an elephant attacking a sugarcane farm]. A negative metaphor cannot be used to describe something as constructive and positive as falling in love with books. You wouldn’t say, “I fell so deeply in love with you that I wanted to tear your clothes off like a wild tiger”. That’s inappropriate and disconnected. Similarly, you could say, “I am so deep in debt, I feel like an elephant charging through my sugarcane farm, destroying my happiness, peace, and calm”. But when it comes to falling in love with books, something like, “I fell in love so deeply with books that I lost myself and felt as though I was being reborn from Saraswati Devi’s womb,” feels more genuine. Just an example but doesn’t it sound constructive and like something a thoughtful writer would say? In Nazriya Nazim’s Ohm Shanthi Oshana, we fall in love with Giri through her eyes over two hours and we fall for her too. So, the climax feels like a deserved twist. Here though, we don’t fall for Sanjay at all. His confession just feels random.

This is the basic level understanding between feeling like expressing what I feel and what feels right from a character’s POV. This differentiates between a writer with skill to use words perfectly and a writer who wants to just try hard. Phanindra Narsetti tried to pour everything that he knew into Manu [2018] and then here he once again got carried away in trying to tell the story of love from a woman’s POV. Ayn Rand’s novels, or any thoughtful writer who genuinely tries to understand the female perspective, can provide more clarity to such a narrative than someone still thinking like a man through a female character. The difference lies in bringing a woman to life on screen, not in breathing life into what feels idealistic to the writer. Remember film is an art form that tries to talk through movies images and those images need depth not just painted colors. Leonardo da Vinci and an aspiring artist might use the same canvas and colors, but only Vinci could create the Mona Lisa. With good production values and spirited music composer Hesham Abdul Wahab, the movie tries to take us to Ayodhya but ends up stopping in Chambal and re-routes to Lanka, where it never truly intended to go.

Theatrical Trailer:

Recent Comments